Same Goal, Different Plays: How Brantford and Sudbury Are Building Their Next Arenas

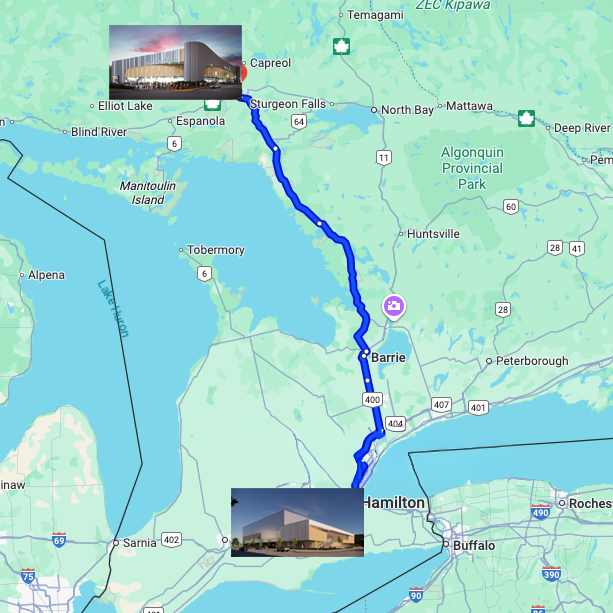

Brantford isn’t the only Ontario city planning a big arena/entertainment centre. While we are in the design and approval stages of the proposed Sports and Entertainment Centre (SEC) at an estimated $140 million, Sudbury is already deeper into its own $200–225 million downtown Event Centre. On paper, the two projects look like siblings: modern OHL-sized arenas, both pegged as catalysts for struggling downtowns. But the financing, timelines, and political context are very different.

TL;DR

- Brantford’s SEC and Sudbury’s Event Centre are similar in size but worlds apart in cost.

- Brantford’s financing hinges on future downtown tax growth and sponsorships, Sudbury is leaning heavily on debt.

- Both cities are banking on downtown arenas as catalysts for revitalization.

- Procurement models differ: Brantford is still shaping its approach, Sudbury has already locked in PCL Construction.

- Success for both hinges on what happens outside the walls – will private development follow?

For Brantford, the SEC is pitched as a bold but manageable play: keep the Bulldogs in town, pull more concerts and events, and use the momentum to encourage other new developments in the surrounding area and finally revive the lower downtown. I’m bullish on that vision, but cautious because without the incremental property taxes from surrounding developments, we might be left footing the bill with fewer revenue streams than planned for.

Sudbury’s story is a few chapters ahead. After scrapping a suburban plan that ballooned past $215 million, they’ve assembled land downtown, approved $135 million in new debt, and already signed PCL Construction to break ground in 2026. Their gamble is bigger financially, but arguably safer in terms of execution: costs are more transparent, public engagement has been robust, and they’re pacing for a Fall 2028 opening.

With all the talk of how expensive Brantford’s proposed SEC is, I wanted to dive into how do the two projects stack up, and what can Brantford learn from Sudbury’s successes and hurdles.

Matt’s Stats

- Brantford SEC: ~$140M budget, ~5,300 seats, 15-year Bulldogs MOU signed, target opening early 2028

- Sudbury Event Centre: ~$200–225M budget, 5,800 seats, $135M new debt approved, target opening Fall 2028

- Cost per seat: Brantford ~$26K vs Sudbury ~$34–39K

- Debt per capita: Brantford (pop. ~106K) ≈ $1,320 per resident vs Sudbury (pop. ~166K) ≈ $813 per resident

- Parking model: Similar with both cities opting for dispersed downtown lots within walking distance

- Procurement: Brantford – model not finalized; Sudbury – PCL locked in as Construction Manager

Brantford’s Sports and Entertainment Centre (SEC)

Location and Vision

Brantford’s SEC will be built at 79 Market Street, adjacent to the Civic Centre. The City is clear about its dual purpose: keep the Bulldogs in town long-term and spark a revival of the lower downtown. The project is framed as a once-in-a-generation investment that ties into broader redevelopment plans for Market Street South and Colborne St E. and the surrounding downtown area

Capacity

Official city documents consistently state the arena will have “a minimum of 5,000 seats” or “over 5,000.” However, local reporting, and consultant reports have put the expected fixed seating for hockey at around 5,300, expandable to 6,600+ for concerts and other events. This aligns Brantford with mid-tier OHL and concert venues across Ontario, which almost doubles the 2900+ capacity at the current TD Civic Centre.

Budget and Financing

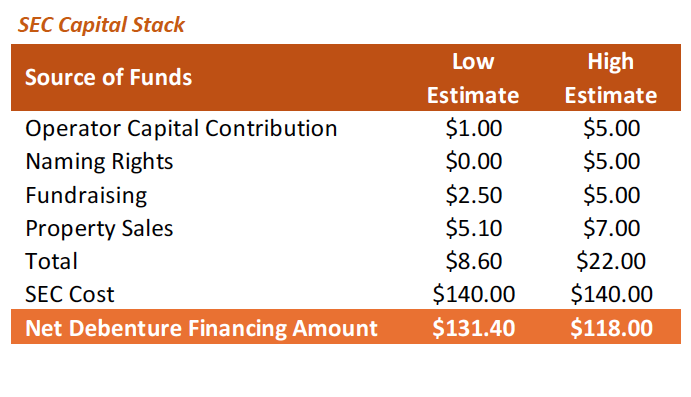

The City’s working budget is pegged at $140 million, with an accepted range of $115M–$140M depending on contingencies. The financing strategy emphasizes not raising residential property taxes directly:

- Incremental tax revenue from growth in the lower downtown (estimated $9M per year once redevelopment builds out)

- Municipal Accommodation Tax (MAT) from hotel stays

- Naming rights and corporate sponsorships

- Casino reserve funds may be partially redirected

This “layered revenue” approach spreads the risk. If downtown redevelopment is slower than projected, naming rights, sale of city property, or casino contributions can help cushion the shortfall. On the flip side, if all of these revenue streams underperform at once, the City may be forced into tax increases.

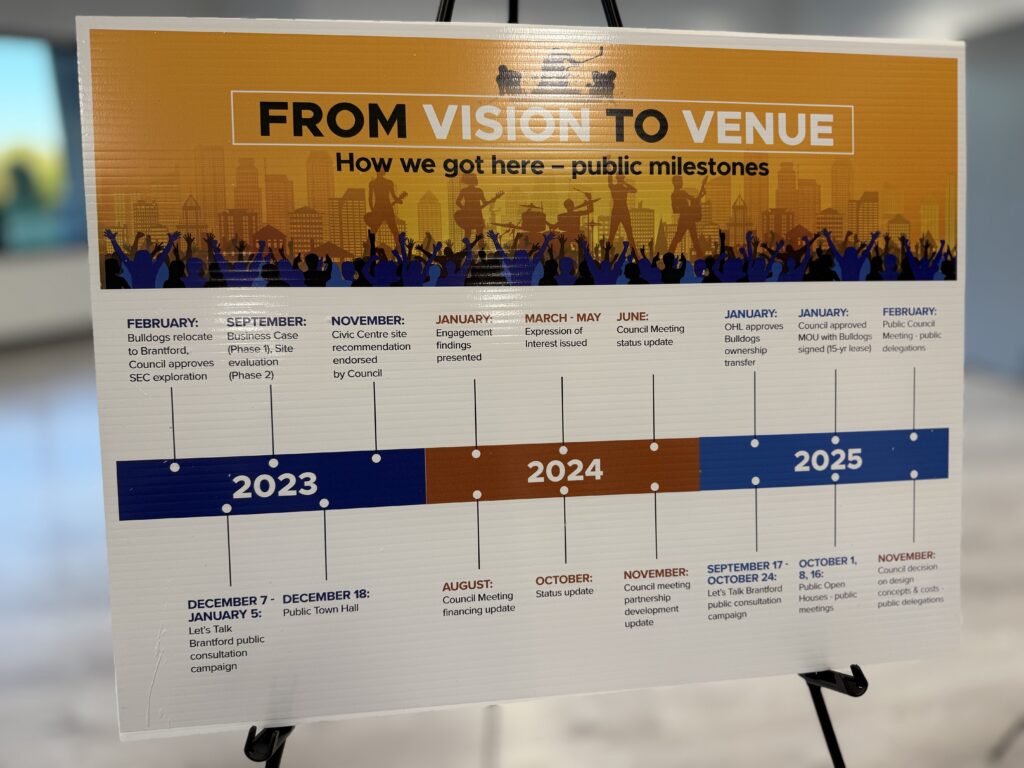

Lease with Bulldogs

A Memorandum of Understanding with the Brantford Bulldogs was signed in January 2025. It lays out the foundation for a 15-year lease with five 5 year extension options, ensuring OHL stability and anchoring the business case for the SEC. This long-term commitment is a clear advantage for Brantford compared to Sudbury, where negotiations are still ongoing.

Why haven’t the Bulldogs signed a lease yet?

Quite simply would you sign a lease if you didn’t know what your house was going to look like? The other elephant in the room is that the TD Civic Centre has always been considered a temporary home for the Bulldogs, with a new arena as the future proof plan to keep the team long term. Once certain design milestones are approved, the lease will most likely be signed by the team.

Timeline

- 2024: Design phase launched

- 2026: Construction expected to begin

- Early 2028: Targeted opening

Sudbury’s Event Centre

Location and Vision

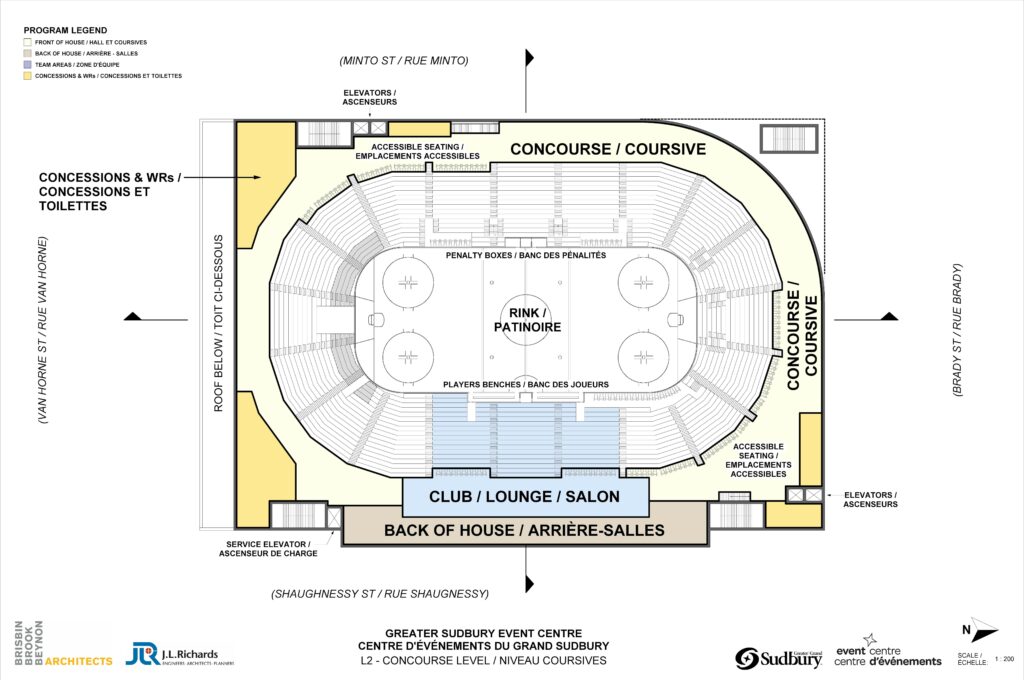

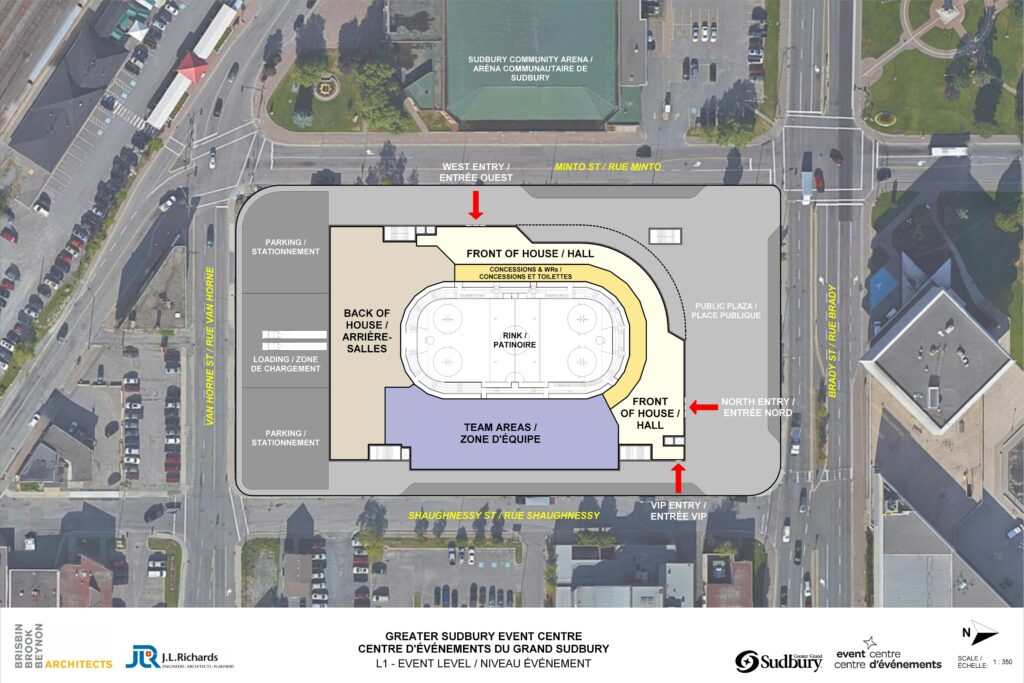

Greater Sudbury’s Event Centre will be built in the “Downtown South” district at Minto and Brady Streets. After abandoning the suburban Kingsway Entertainment District plan in 2022 due to ballooning costs, Council pivoted to downtown with the goal of pairing the arena with broader revitalization projects like the new Cultural Hub (library/art gallery).

Budget and Financing

Council approved a $200 million budget in April 2024, though by September 2025 estimates had crept closer to $225 million due to inflation. Financing rests heavily on debt:

- $135 million in new debt authorized

- Existing borrowed funds from the cancelled Kingsway project partially reallocated

- MAT revenue earmarked for debt servicing

- City staff committed to quarterly budget updates and have emphasized that contingencies for soil and inflation are already included

This model is straightforward but debt-heavy. The upside: Sudbury has fewer moving parts. Once Council authorized the debt and MAT allocation, funding certainty was achieved and contractors had confidence to proceed. The downside: the City carries the debt on its books immediately, limiting capacity for other priorities and exposing residents if MAT revenues fall short.

Capacity

The official figure is 5,800 fixed seats for hockey, with flexibility to accommodate more for concerts and other events. The design includes a mix of bowl seating, club seats, loge boxes, and 20 private suites. This makes Sudbury’s centre slightly larger than Brantford’s, but still in the OHL mid-market range.

Lease with Wolves

Negotiations with the Sudbury Wolves are ongoing. The team has signalled support for the project, but as of late 2025 no long-term lease had been finalized. This is a key risk factor compared to Brantford’s Memorandum of Understanding with the Bulldogs.

Timeline

- 2023: Land assembly completed downtown

- April 2024: Council approved new build

- Sept 2025: Renderings unveiled, PCL signed as Construction Manager

- Late 2025: Site prep begins

- 2026–2028: Main construction

- Fall 2028: Targeted opening

How Do The Brantford and Sudbury New Arenas Measure Up?

Cost per Seat

Brantford: With a working budget of about $140 million and a planned capacity of around 5,300 seats for hockey, the cost per seat comes in at roughly $26 400. If you include expanded capacity for concerts and shows (estimated at 6,600+), the ratio improves a bit, but hockey capacity is the baseline for comparison.

Sudbury: Sudbury’s Event Centre has an approved budget of $200 million and 5,800 fixed seats, which translates to a cost per seat of about $34,500. If the budget creeps toward $225 million, as some projections suggest, that number climbs to roughly $39,000 per seat.

Brantford’s SEC has a lower cost per seat than Sudbury’s Event Centre, placing it on the more efficient end of current mid‑market arena projects. Both are much more expensive per seat than older Ontario arenas built in the early 2000s (which cost closer to $6,000–$10,000 per seat), but construction costs have obviously risen sharply since then.

Debt per Capita and Tax Impact

Brantford: Brantford has about 106,000 residents. If the city were to borrow the full $140 million for the SEC, that works out to roughly $1,320 per person. The plan, however, isn’t to dump that entire burden on taxpayers. City staff have said they will offset borrowing costs through a mix of downtown tax uplift, Municipal Accommodation Tax (MAT) revenues, naming rights, and the sale of city‑owned properties. This layered approach should keep property taxes in check, but it depends on new downtown development and sponsorship deals coming through. If those revenue streams lag, the debt could still end up on the tax bill.

Sudbury: Greater Sudbury has a population of around 166,000. Council has approved $135 million in new debt for its Event Centre, which equals about $813 per resident. Sudbury’s approach is more straightforward: borrow the money, use MAT revenue to help pay it back, and provide quarterly updates to Council. It’s less creative than Brantford’s plan, but it does give the city a more predictable financing path. If the budget creeps up to $225 million, the per‑person cost would rise, though it’s still below Brantford’s ratio because Sudbury has a larger tax base.

Brantford’s financing model feels lighter to taxpayers because it leans on future growth and sponsorship dollars, but it carries more risk if those revenues don’t materialize. Sudbury’s debt‑heavy plan is simpler and more certain, but it means residents are on the hook from day one.

Downtown Revitalization Impact

Brantford: This project isn’t just about hockey, aside from hosting a litany of other events, conferences, trade shows, concerts, etc., it’s meant to breathe life into the lower downtown. Vacancy or turnoverrates are still high, and a lot of the land around Market Street and Colborne Street East is underused or waiting for something to happen.

This project will be the spark plug for the developers that are waiting in the wings with planned projects in the same area. That’s the dream. The risk / worst case scenario is if the private developments that have been waiting on this decision do not come to fruition.

Sudbury: Sudbury’s strategy goes wider. Their Event Centre is part of a larger rebuild that includes a Cultural Hub, new public spaces, and a plan to fill cleared downtown blocks with mixed-use projects. The goal is constant activity – art and library visitors by day, hockey and concerts by night. It’s civic design as a full-court press.

It also means higher stakes. When you build everything at once, you get energy and momentum, but you also carry the risk that one delay slows the whole thing down.

Brantford’s putting one big spark downtown and hoping it catches. Sudbury’s lighting the whole matchbook. Ours is leaner, faster, and more focused on one anchor tenant. Theirs is larger and more coordinated. Both cities are trying to prove the same thing… that a new arena can change the story of a downtown.

Parking and Transportation

Brantford: The SEC’s parking plan relies on using the existing supply downtown. There are more than 1,500 public parking spaces within a five‑minute walk, including nearly 500 on‑street spots and several municipal lots. The biggest asset is the Market Centre Parkade, a three‑level garage with roughly 941 spaces just north of Market Street. It’s most likely that this parkade will be the go‑to garage on game and concert nights. (It already offers free parking during Bulldogs games.) The city hasn’t announced any new parking construction or major transit upgrades, so success will hinge on good signage, lighting and pedestrian routes, and on whether that existing supply can handle big event nights.

Sudbury: Greater Sudbury plans to continue the dispersed parking model it uses for the current arena. City FAQs note there are 14 surface lots and one underground lot downtown, providing 2,182 public parking spaces; when nearby private lots are included, the total rises to 3,648 spaces. Rather than building a new garage, the city expects event‑goers to park in these existing lots and walk a few blocks. This avoids a big capital cost but depends on people being willing to walk and on those lots being available when events are on.

Both cities are choosing to leverage existing parking instead of building new structures. Brantford’s supply is smaller, so it will need to manage demand carefully and perhaps encourage more transit or rideshare use. Sudbury has a larger pool of spaces, giving it more breathing room. In both cases, wayfinding, lighting and pedestrian safety will be key to making the walk from lot to arena feel comfortable.

Event Versatility and Utilization

Brantford: This isn’t going to be just a hockey rink. The SEC is designed to seat around 5,300 for hockey and can expand to roughly 6,600 for concerts and other shows. The long‑term lease with the Bulldogs gives the venue a strong anchor tenant. But the real win will be if Brantford can fill open dates with mid‑sized concerts, family shows, and community events—acts that often skip over us on their way between Hamilton and Toronto. Early talk about making the building flexible enough for everything from ice shows, trade shows, food and drink events, concerts and conferences. How well that plays out will depend on how aggressive the booking strategy is and whether promoters see Brantford as a viable stop.

Sudbury: Sudbury’s Event Centre is slightly bigger, with 5,800 fixed seats and room to add more for larger events. It includes a mix of bowl seating, club seats, loge boxes and suites, aiming to attract not just hockey and small concerts but touring acts that need a mid‑size Northern Ontario stop. The city has positioned it as a regional hub for sports, concerts and community events. Premium seating and suites should help drive revenue and lure bigger shows, but the market will have to support enough events to fill that capacity.

Sudbury’s scale and premium options give it a shot at drawing bigger, more diverse events. Brantford’s advantage lies in locking down the Bulldogs and targeting spillover acts that might otherwise bypass us. Success for both cities will hinge on aggressive event booking and creating a facility that works just as well for concerts and family shows as it does for hockey.

Procurement and Inflation Risk

Brantford: In February 2025, City Council voted to use a progressive design‑build model for the SEC. That means hiring a single team to design and build the arena together, rather than bidding each part separately. The goal is to reduce risk, improve collaboration and give the City more say in cost control. Brantford has already issued a request for qualifications and begun releasing tender packages for early work like concrete foundations. But until a full contract is signed, inflation is still a threat. The longer the City waits to lock in prices, the more material and labour costs could climb.

Sudbury: Sudbury locked in its construction partner in September 2025 when it hired PCL Construction as the Construction Manager. Under this model, PCL works with the City and the architects to manage design and costs, with quarterly budget updates to Council. This approach gives Sudbury more tools to handle inflation and supply chain surprises, but it doesn’t eliminate cost risk altogether—especially if construction markets stay hot.

Sudbury is ahead of Brantford on procurement. It has a builder in place and a process for monitoring costs. Brantford needs to finalize its design‑build team soon to avoid being caught by rising construction prices.

Operations, Lease Strength, and Revenues

Brantford: The biggest win for Brantford is certainty. In January 2025, the City signed a 15‑year Memorandum of Understanding with the Brantford Bulldogs, with options that could extend the agreement up to 40 years. That anchors the arena’s business case: we know there will be OHL hockey here for the long haul, which means steady ticket sales and a built‑in fan base. It also gives the community something to rally around. The City hasn’t announced naming rights or major corporate sponsorships yet, so those are still untapped revenue streams that could help offset costs.

Sudbury: Sudbury isn’t there yet. The City and the Sudbury Wolves have been negotiating a long‑term lease, but as of late 2025 nothing had been finalized. The team is supportive of the new event centre, but until a contract is signed there’s no guarantee they’ll stay long term. On the revenue side, Sudbury’s design includes premium seating like club seats, loge boxes and suites, which can command higher prices and bring in more money over time. That gives them a chance to out‑earn Brantford on per‑seat revenue if the market supports it.

Brantford has locked in its anchor tenant, which means predictability and community buy‑in. Sudbury has more uncertainty on its lease but more upside from premium seating. The revenue equation in Sudbury could look better in the long run if the Wolves commit and the market fills those high‑end seats.

Accessibility and Community Use

Brantford: The SEC’s community‑use details haven’t been spelled out yet. The city has mentioned that it will host public skating, minor hockey tournaments, and flexible event spaces, but full programming plans are still to come. Whatever the final design looks like, it will need to meet modern accessibility standards so every fan can enjoy the building. That means fully accessible seating, concourses, and amenities that comply with OHL requirements and the Ontario Building Code.

Sudbury: Sudbury’s Event Centre is being designed with accessibility front and centre. The city’s FAQ emphasizes features like wide concourses, universal seating options, and inclusive design. They also note that Indigenous engagement has been part of the planning process. By baking those elements in from the start, Sudbury is trying to create a venue that works for everyone, not just sports fans.

Sudbury has put accessibility at the heart of its new arena. Brantford will need to show the same commitment to inclusive design and community programming if it doesn’t want to fall behind public expectations.

Ontario Comparables: Meridian Centre and Canada Life Place

To put Brantford and Sudbury in context, it helps to look at two other mid‑sized Ontario arenas built in the last two decades: St. Catharines’ Meridian Centre and London’s Canada Life Place (originally Budweiser Gardens). They show what’s possible when a new arena anchors downtown.

Meridian Centre (St. Catharines)

Opened in 2014, the Meridian Centre seats about 5 300 for hockey and up to 6 000 for concertsen.wikipedia.org. It cost roughly $50 million to builden.wikipedia.org. That’s about $9 400 per seat at 2014 prices – far cheaper than Brantford’s and Sudbury’s projects, but construction costs have risen sharply since then. The arena has 20 private suites, club seats and a flexible bowl, and it helped rejuvenate St. Catharines’ downtown by drawing the Niagara IceDogs and mid‑sized concerts. Its naming rights deal with Meridian Credit Union offsets operating costs.

Canada Life Place (London)

London’s downtown arena opened in 2002 as the John Labatt Centre, later renamed Budweiser Gardens and then Canada Life Place. It seats 9 036 for hockey and up to about 9 000 for concerts. The project cost roughly $42 million for construction plus $10 million for land, for a total around $52 million. Even with inflation, that works out to roughly $5 800 per seat which is extraordinarily cheap by today’s standards. The City of London contributed about $32 million to construction and $10 million for the land, while private partners covered the rest. The arena’s success has been anchored by the London Knights hockey team and a steady stream of concerts and events.

How They Compare

Cost Efficiency

Both older arenas were built for far less money per seat than Brantford’s and Sudbury’s projects. The Meridian Centre cost about $9 400 per seat, and Canada Life Place roughly $5 800 per seat, compared with $26 400 per seat for Brantford and at least $34 500 for Sudbury. Rising labour and material costs explain part of the gap, but it shows how expensive new builds have become.

Scale

Meridian Centre’s capacity is in the same range as Brantford’s SEC and Sudbury’s Event Centre, while Canada Life Place is almost twice as large. This gives London flexibility to host bigger acts, but also means higher operating costs.

Downtown Impact

Both arenas helped to catalyse downtown revitalization. Meridian Centre integrated with St. Catharines’ downtown renewal and waterfront projects. Canada Life Place kick‑started London’s downtown entertainment district and has consistently ranked among the top‑grossing venues of its size in Canada.

These comparables show that success isn’t just about seat count or budget. What made Meridian Centre and Canada Life Place work was a combination of strong anchor tenants, steady event programming, and coordinated downtown planning. Brantford and Sudbury will need to ensure their arenas plug into broader downtown strategies and not rely solely on hockey to drive foot traffic.

What Could Go Wrong With Brantford and Sudbury’s New Arenas: Wildcards and Risks

No arena project is risk‑free, and both cities have a few potential trip‑ups that could throw off their plans.

Cost overruns and inflation

Construction costs have been volatile for the last few years. Sudbury has already seen its estimated budget creep from $200 million toward $225 million, and Brantford hasn’t put its project out to tender yet. If material prices or labour costs spike, both cities could face higher bills than they expect. Sudbury’s construction manager model gives it better tools to manage inflation, but it doesn’t guarantee there won’t be surprises. Brantford’s progressive design‑build approach is supposed to control costs, but until a contract is signed, prices are still at the mercy of the market.

Lease Uncertainty

Brantford has locked in the Bulldogs for 15 years, with extension optionsbrantbeacon.ca, giving the project a solid anchor tenant and predictable revenue. Sudbury hasn’t yet signed a long‑term lease with the Wolves. If negotiations stall or the team leaves, the Event Centre would lose its primary tenant and a big chunk of its revenue base. A last‑minute exit might also undermine public confidence in the project.

Downtown Development Lag

Brantford’s financing plan counts on new downtown development generating about $9 million a year in extra tax revenue and on corporate sponsorships and naming rights. If developers hesitate, if interest rates keep rising, or if the broader economy slows down, those dollars might not materialize on schedule. Sudbury’s plan isn’t dependent on private development in the same way, but its broader downtown revitalization aims could stall if other civic projects (like the Cultural Hub) face delays or cost pressures.

Community Buy‑In

Both arenas rely on drawing not just hockey fans but also concertgoers, families, and tourists. If the public feels the buildings are too expensive or the programming isn’t diverse enough, ticket sales could lag. In Brantford, local opinion is generally bullish but cautious; in Sudbury, the long debate over the Kingsway plan created some lingering skepticism. Keeping residents engaged and excited will be key.

Future Interest Rates and Debt Load

Sudbury’s debt‑heavy plan locks in a lot of borrowing. If interest rates rise or if economic conditions change, debt servicing could eat more of the city’s budget than expected. Brantford’s diversified approach spreads the load, but if multiple revenue streams underperform at once, the city may still end up leaning on taxpayers.

Construction Delays

Any major project can run into unexpected site issues. Sudbury has budgeted contingencies for soil conditions in the downtown site, but unexpected problems could still slow down the build. Brantford’s project hasn’t broken ground yet, so unknown site conditions or environmental remediation could cause delays once work begins.

Politics and Public Opinion

Municipal elections, shifting council priorities, or provincial funding changes could affect timelines and budgets. A surprise referendum in Brantford (if someone successfully calls for one) or another major vote in Sudbury could add uncertainty.

These risks don’t mean either project is doomed, but they underscore why clear planning, transparency, and adaptability are essential. Knowing what could go wrong makes it easier to plan for success.

Brantford and Sudbury are both betting on these projects to change the fortunes of their downtowns. Brantford’s Sports and Entertainment Centre looks leaner on paper and benefits from almost locked‑in Bulldogs lease. Sudbury’s Event Centre is bigger and carries more debt, but it’s part of a coordinated downtown rebuild. Both cities are hoping the same thing: that people will come, spend, and spark a broader transformation.

As a Brantford resident, I’m optimistic but realistic. The SEC could be the catalyst we’ve been waiting for, but only if the condos, multi-use facilities and other planned developments fill in around it and help pay the bills. Sudbury’s plan shows how a city can pivot when an original site doesn’t work, but it also shows the financial weight that comes with a debt‑heavy approach.

If everything falls into place, both arenas could become case studies in how mid‑sized Canadian cities reinvent themselves. If they stumble, they’ll be cautionary tales. For now, the puck is on the ice and the game is just getting started.

Some of the sources used for this article: City of Brantford – Council report, City of Brantford, Sudbury.com, Greater Sudbury FAQs, CTV Northern Ontario coverage